After a couple of days of lousy weather, the sky cleared up and dried out Wednesday. Eventually, we got down to τ<0.08 — not quite the best possible conditions, but good enough for almost anything we might want to do. We started out slightly worse than that, but that meant we got to observe more interesting things: nearby bright, big galaxies. Unfortunately, a galaxy that is bright and big in visible light is still just a blob in the submillimetre (submm). Our first one was NGC 3034, aka M82, exciting for two reasons. First, it’s the prototypical starburst galaxy, a galaxy undergoing a rapid period of star formation, gobbling up gas and dust and turning them into stars, which in turn heat up the remaining dust, making the galaxy glow brightly in the infrared and submm. Second, M82 is the home of a recent supernova explosion, the nearest one since 2004, and the nearest one of the particularly important type Ia since 1972. And it was first discovered by students at University College London, right across town.

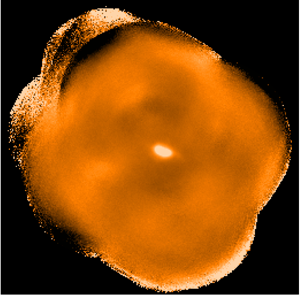

So, I am sure that you are very excited to see a beautiful picture of the galaxy, at right. The elongated blob in the center isn’t even the whole galaxy:

that’s the bright nucleus glowing from the concentration of star formation there. I think — and my proper observational-astronomer friends will correct me if I’m wrong — that some of the dark fuzz around the nucleus is really part of the galaxy, which would take up most of this picture, about 15 arc minutes from top to bottom.

that’s the bright nucleus glowing from the concentration of star formation there. I think — and my proper observational-astronomer friends will correct me if I’m wrong — that some of the dark fuzz around the nucleus is really part of the galaxy, which would take up most of this picture, about 15 arc minutes from top to bottom.

After M82, we observed another nearby galaxy, the somewhat less famous NGC 4559, and then conditions improved enough that we could do observations as part of the SCUBA-2 Cosmology Legacy Survey (CLS), which is officially why I’m here. But that’s a lot less fun, as it’s just observing more or less blank patches, again and again, building up a deep submm survey of large areas of sky (where for these purposes, “large” just means about 35 square degrees, out of about 41,000 on the whole sky). We repeat each small patch dozens of times, adding them up and building up pictures so dense with galaxies that they are said to be “confusion limited” — the main source of noise is just the population of galaxies themselves, individually too faint to see, but contributing to the infrared background light everywhere we look (this depends on both the wavelength of the light and the resolution of the telescope — that is, the size of the smallest object that you can make out.).

For the rest of the night, through until dawn, we kept on observing the CLS fields, and have started back onto them today, in even better conditions than yesterday.

So far, I’ve been pleasantly surprised about life at 14,000 feet: there is definitely less oxygen than down at sea level (or even than Hale Pohaku at 9,000 feet where I sleep and spend the days), but I’ve been spared the worse symptoms of altitude sickness. And jet-lag, combined with strong and good coffee provided by the excellent Telescope System Specialist (TSS) has meant that staying up through until 7 or 8am hasn’t been too bad. (On the other hand, re-reading this post leaves the impression that my ability to string a sentence together has been somewhat impaired by the lack of sleep and oxygen…)

In fact, the TSS is really the one doing — quite literally — all of the work here. Because we are observing as part of the JCMT Legacy Survey, there’s nothing for the “observer” (i.e., me) to do. Later on, the survey team will collate the data that have been gathered and make the final images and catalogs, but that’s a slow and painstaking process, not one that happens on the night the data are taken. And taking the data is such a complicated task that only the Specialist really has the expertise to do it. He keeps me informed of what’s going on, but I don’t really get much of a say in what happens.

You may ask why someone spends the money to send us astronomer/observers across an ocean or two to stay up at night, drink coffee, and not really do any science. Gift-horses aside, so do I.

But it certainly is a gift and a privilege to be here: